If you're stuck, let go of your rigid vision

There’s a certain face-hitting-rake that I keep stepping on.

(psst… if you want to listen to me read this to you, click above! ^)

There’s a certain face-hitting-rake that I keep stepping on. I’ll have an idealistic vision of how things should be, and I’ll cling to that vision so tightly that I’m unable to make progress. This has happened quite often, and at basically every timescale.

A short example. For writing this essay, I’ll have some vision of the mythical great essay. The requirements for this are myriad and conflicting: it’ll be vulnerable, but not cringe; it’ll build towards a logical conclusion, but won’t feel formulaic; it’ll be neither too long nor too short. The draft gets stuck in development hell.

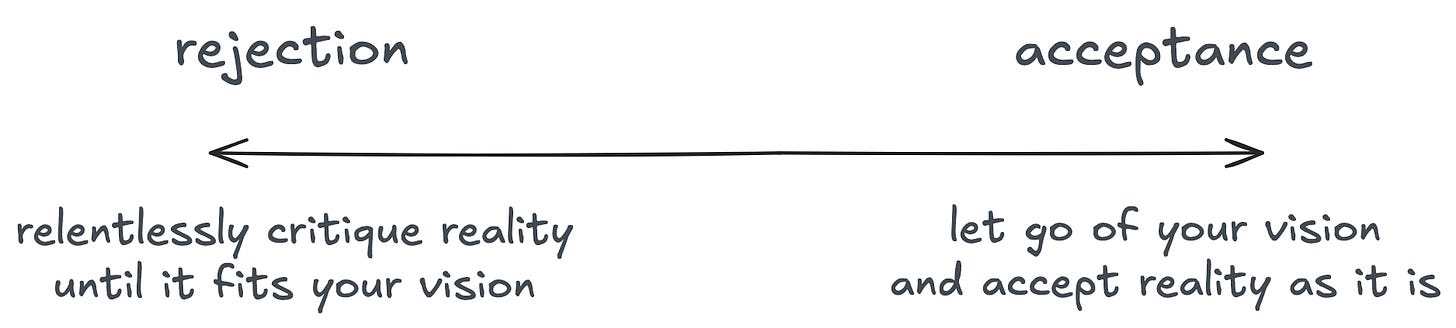

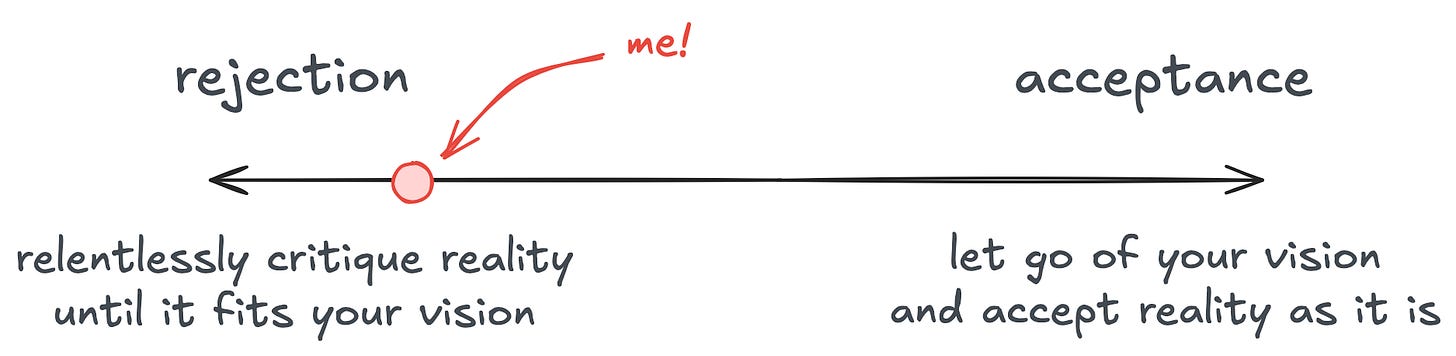

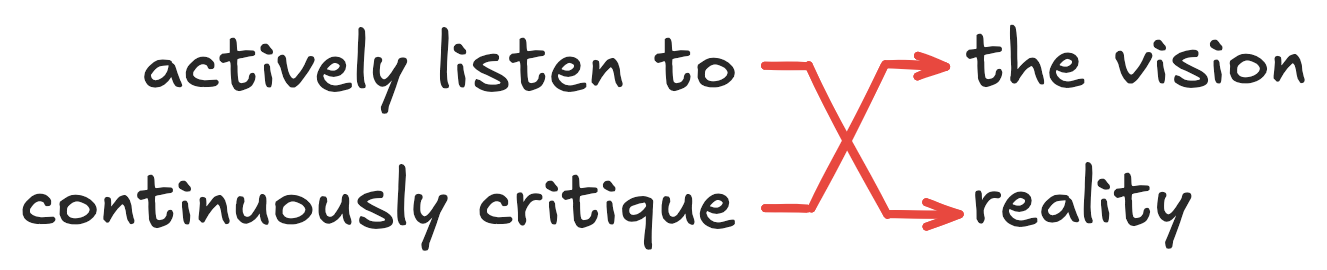

When these visions enter your mind, your attitude will lie somewhere between:

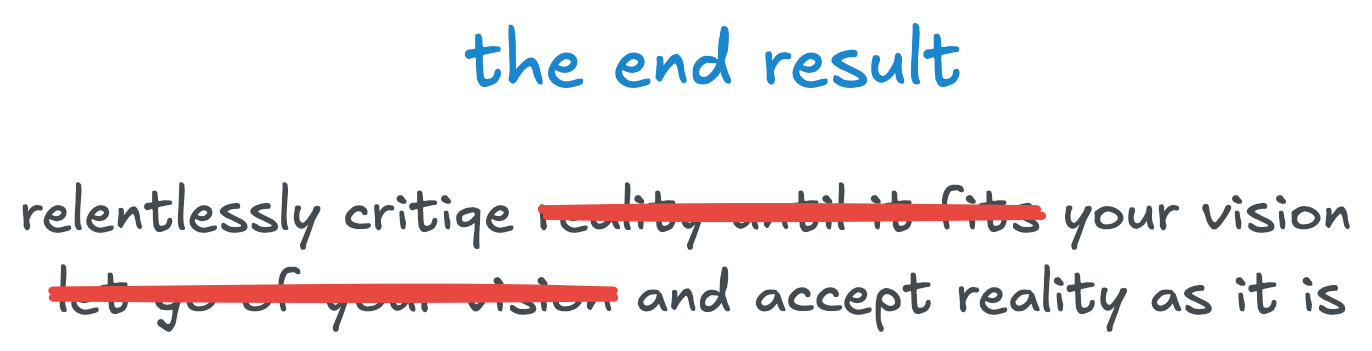

relentlessly critiquing reality until it fits your vision, or

letting go of your vision and accepting reality as it is.

I don’t think that one attitude is inherently better than the other. What I do think is that I was the kind of person who defaulted to Attitude 1—or, at least, what I thought was Attitude 1—regardless of whether or not it was actually serving me.

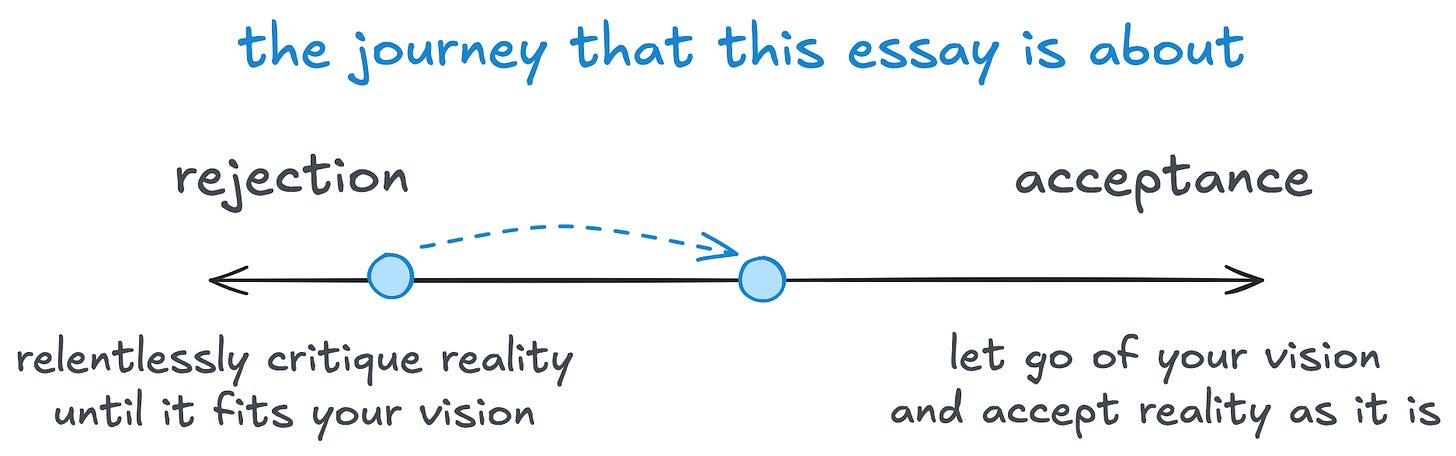

As you’ll see in the next section, I ended up pretty stuck. What helped me get unstuck was borrowing a few tools that live in Attitude 2. So today’s story is about my journey from Attitude 1 towards Attitude 2, and how I ended up somewhere in the middle.1

Let’s begin with this: what do I mean by rigid vision?

Hitting Myself in the Head with a Cast Iron Pan

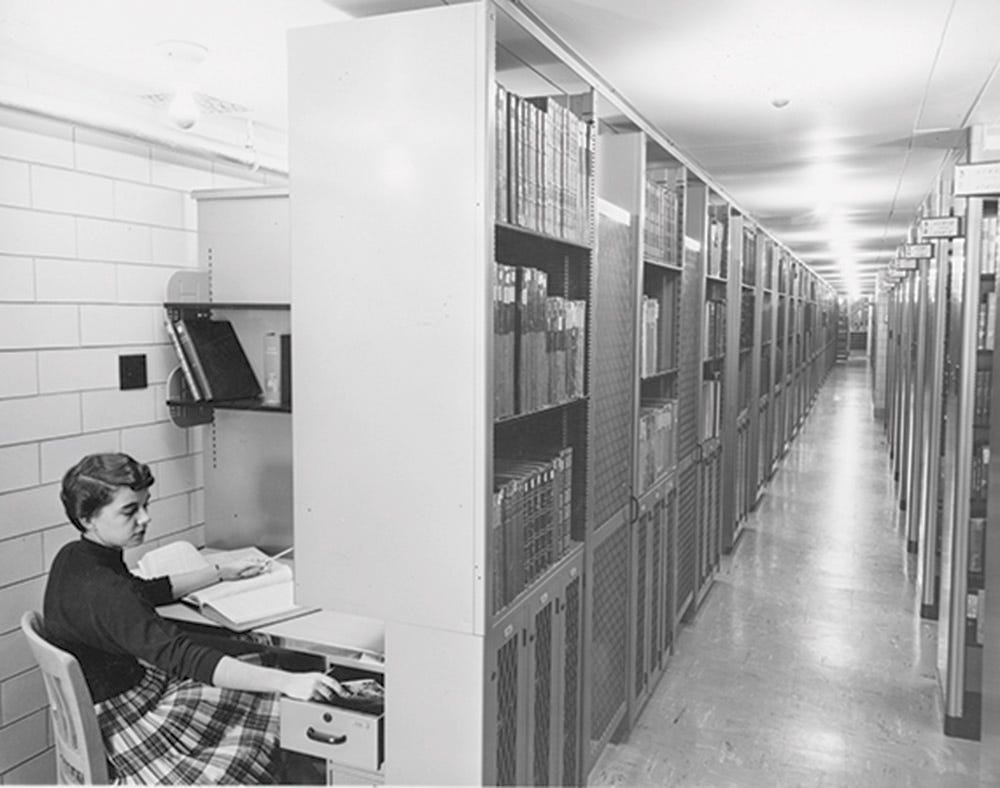

Freshman year of college. I had read Deep Work by Cal Newport, Ultralearning by Scott Young, and enrolled in a course by this guy who claimed to have uncovered the perfect study system. The vision was clear: I’d wake up at 6 AM, lock myself in the Memorial Library cages, and get perfect grades. I was going to take college seriously, and learn better.

It was a cause for great self-hatred when I discovered that this was really difficult. Forget “continuously asking mental questions in lecture”, I was struggling to stay awake! Visions of hours-long study sessions where I Locked The Fuck In slammed into the brick wall of I Just Seem To Be On My Phone All The Time. And it seemed that no habit change would stick; I would make plans for the next month, then the next week, then the next day, until eventually I gave up trying altogether.

I was so hyperfocused on the vision that whenever I encountered something that wasn’t exactly it, I could only see its flaws. I was blind to small wins: each and every study session could’ve been done more effectively, so they were failures. I was so focused on being a critic that I was unable to create.

I really only paused when reality hit. In my case, reality hit in the form of a glowing, neon F on my multivariable calculus final. It was here that I first seriously considered letting go of my vision.

But the very idea of “letting go of my vision” seemed like loser behavior. I would be lowering my standards. What, was I supposed to just accept that I shouldn’t build an efficient study system? Was I supposed to accept that I’d be unemployed at the end of college? That means giving up. No, thank you. I don’t think you understand how badly I want this. I think I’ll double down.

Gently Listen, Relentlessly Question

I hope that you can see that this misses the point entirely. I was not asking myself to let go of my standards, merely the unrealistic ones. I was not asking myself to give up, I was asking myself to give up on this one specific thing, when achievable alternatives exist.

I dearly wish I could sit my freshman self down in a metal folding chair, give him a glass of water, and gently explain to him that he was going about things backwards.

“Listen up, dude,” I’d say. “This clearly isn’t working. You’re frantically pointing out the flaws in reality, when what you need to do is slow down and listen to it. You’re blindly following the siren call of your vision, when what you need to do is question it deeply.”

Okay, older, wiser, and more handsome me. What does that mean, exactly?

It means listening to reality the same way you listen to the people you love. Listen to it deeply, with compassion, and without reservation. Reality has a surprising amount of detail, so it’s going to have a lot to say. There’s so many details, in fact, that it won’t ever fit your vision perfectly, so stop waiting for it to fit to consider yourself to have made progress.

Let things unfold. Run experiments. Do your best to clearly see what works and run with it, and cut off the things that aren’t working. This process is going to take time, so be patient with it.

As for your vision: recognize that it has you in a headlock. Reverse that! Relentlessly ask it questions. Demand it to be specific, otherwise you will refuse to materialize it. You’re allowed to let go of the vision, not in totality, but more in a Theseus's ship sort of way: you’ll let go of the individual asks, and in the end, it will be your vision, your desires.

Constantly engage in that process of disentangling what you want from what you think you want, so that you don’t lose yourself in the weeds. Trim away the pieces that you don’t need, and find the win-win.

I’m going to be frank. It’s going to be really hard to do this, especially for someone who serially does the opposite. Your ego and identity will get in the way.2 For you, this is a form of staring into the abyss, which means you’ll procrastinate on this like no tomorrow. But you must do it, because you have no other choice. So find a way.

Paint What You See

If I had to boil this essay down into a single sentence, it’d be the lesson that I learned in Ms. Martinelli’s 4th grade art class, when we were introduced to still life painting. You must paint what you see, not what you think you see.

I surrendered my rigid vision.3 I let it go. I decided to find study techniques that worked, rather than what I thought would work. It turns out I actually show up to study sessions when I meet with other people, so I began organizing those. And you know what? They were fun and productive and I showed up to them every single time! This was me becoming unstuck, and it looked nothing like my vision.

So if you have a vision of the Perfect Thing—the Perfect Life, the Perfect Partner, the Perfect System, whatever—and that Perfect Thing is so viscerally clear to you, it’s divine, it has appeared to you, fully manifested, from the Platonic world of Forms; just please, please understand that the price of manifesting this ideal is to take your precious vision and shove it through a meat grinder. The act of bringing something into being requires the acceptance of pockmarks and acne and dirt and grime; you must take your rigid standards to the grave, and raise up whatever is left with your bare, mud-caked hands.

I am afraid that what comes from this will not be perfect. But it will be beautiful, because it will be real.

This essay was written from the perspective of someone whose go-to was Attitude 1, when, in hindsight, I needed more of Attitude 2. In the spirit of reversing any advice that you hear, it may be the case that you are too good at letting go of your visions, and you should instead take lessons from those who relentlessly critique reality. I can only speak to my own experiences, and so this essay is not written from this perspective. Maybe someone else has written about it. And if nobody else has written about this yet, then perhaps you could! I would love to read it.

If you relate very heavily to this archetype of really having difficulty making tradeoffs and being attached to ideals, consider checking out The Problem of Puer Aeternus, by Marie-Louise von Franz. I was introduced to this concept through two live streams from this YouTube channel I follow. Check out Part One, and Part Two.

I couldn’t find a way to organically work it in, but there’s this quote from Cheryl Strayed’s book, tiny beautiful things, that so perfectly describes this phenomenon that I was inspired to turn it into a graphic. Also, her writing is phenomenal. I recommend this book.

These are good thoughts. I appreciate these thoughts.